America – Cradle For The Second Coming Of The

Christ

Chapter II

How America Became The Cradle For the

Second Coming of the Christ

Puritans Become Pilgrims

One of

the least materialistic and therefore most persecuted religious groups in

England during the early 1600's was the Puritans. Why were they called

Puritans? They were called Puritans because they hoped to restore Christianity

to its "ancient purity." Because they sought to separate themselves from the

temptations of the world, some of them came to be called "Separatists." One of

the least materialistic and therefore most persecuted religious groups in

England during the early 1600's was the Puritans. Why were they called

Puritans? They were called Puritans because they hoped to restore Christianity

to its "ancient purity." Because they sought to separate themselves from the

temptations of the world, some of them came to be called "Separatists."

Hoping to find a place where they could worship without fear

of persecution, a group of Puritan Separatists took temporary refuge in

Holland. Among the Dutch the persecution was less, but these Puritans found

themselves still surrounded by secular pressures and temptations. After a short

time, perhaps a dozen years, they decided to move to the New World to America,

the vast land across the Atlantic Ocean journey of faith that would earn them

the name Pilgrims.

The Pilgrims Leave Holland

For the voyage back to England the Pilgrims purchased a

small ship named Speedwell. It is interesting to note that "Speedwell" is a

common name for the flower "Veronica" which is connected with the legends of

St. Veronica, who was believed to have wiped the face of Jesus on his way to

the cross, receiving the imprint of his face on her kerchief.

A "chronicle of those memorable circumstances of the year

1620, as recorded by Nathaniel Morton, keeper of the records of Plymouth

Colony, based on the account of William Bradford, sometime governor thereof"

describes the Pilgrim's departure from Holland on the first leg of their

voyage:

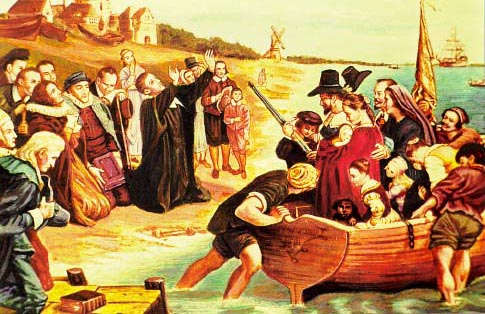

So they left that goodly and pleasant city of Leyden,

which had been their resting place for above eleven years, but they knew that

they were pilgrims and strangers here below, and looked not much on these

things, but lifted up their eyes to Heaven, their dearest country, where God

hath prepared for them a city (Heb. XI, 16), and therein quieted their

spirits.

When they came to Delfs-Haven they found the ship and

all things ready, and such of their friends as could not come with them

followed after them, and sundry came from Amsterdam to see them shipt, and to

take their leaves of them. One night was spent with little sleep with the most,

but with friendly entertainment and Christian discourse, and other real

expressions of true Christian love.

The next day they went on board, and their friends with

them, where truly doleful was the sight of that sad and mournful parting, to

hear what sighs and sobs and prayers did sound amongst them; what tears

did gush from every eye, and pithy speeches pierced each other's heart, that

sundry of the Dutch strangers that stood on the Key as spectators could not

refrain from tears. But the tide (which stays for no man) calling them away,

that were thus loath to depart, their Reverend Pastor, falling down on his

knees, and they all with him, with watery cheeks commended them with the most

fervent prayers unto the Lord and His blessing; and then with mutual embraces

and many tears they took their leaves one of another, which proved to be the

last leave to many of them.

The Pilgrim's tearful departure from

Holland

Farewell to England

The good ship Speedwell carried its passengers safely back

to England where they assembled in July of 1620 to make their final plans for

the daring venture. At the insistence of the financial backers of the voyage,

the Pilgrims were joined by other farmers and tradesmen, who also sought a

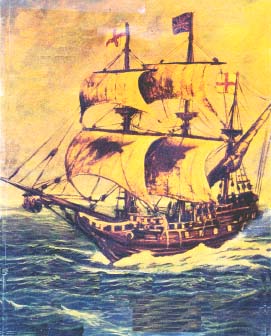

better life in America. A second ship, the Mayflower, was acquired and William

Bradford became the group's leader. When all was ready the Pilgrims boarded two

ships, but it quickly became obvious that the Speedwell was not seaworthy for

the longer trip to America. It leaked so badly it had to be abandoned, and its

passengers crowded onto the Mayflower.

On September 16th, 1620, the Mayflower, crammed with 102

Pilgrims and other passengers seeking a new life in America, sailed from

Plymouth, England "into the pages of history."

The departure caused little stir. Great things often happen

when we do not realize it. One night angels sang over the Bethlehem hillsides

and only a few shepherds heard it and were led to the stable where Jesus was

born. Centuries later in 1775, when Paul Revere set out on his midnight ride,

who knew that "the fate of the nation was riding that night?" Just so, in 1620,

when the Mayflower pulled away from English shores, no one knew that a

new era was beginning.

The Crossing

The horrible overcrowding of the small Mayflower made the

Atlantic crossing a nightmare. Midway across the Atlantic the Mayflower was

engulfed in a storm that terribly threatened the vessel. Huge waves tossed the

boat about, heaving and writhing under shrieking, screaming winds that

threatened to tear the masts from the deck. Seasick passengers shivered below

decks, wondering if the gigantic waves would topple the ship.

"He who hesitates is lost," says the old adage. At this

moment, considering the trials they endured and those still ahead, the Pilgrims

might have been tempted to say, "He who hesitates is probably right." But

the Pilgrims did not hesitate. The Mayflower sailed on and the fate of

a nation, the destiny of untold millions yet unborn, sailed with them.

Land!

On November 19, 1620, a shout went up: "Land!" Everyone

rushed on deck. Barely visible many miles away a strip of shoreline could be

seen. The Pilgrims dropped to their knees and wept with joy, thanking God.

After sixty-six days and nights on the Atlantic, God had delivered them to the

New World.

Two days later the vessel reached Provincetown Bay in

Massachusetts. As the ship found its way to the vast bay and dropped anchor the

Pilgrims saw stretching before them a dark forbidding wall of forest.

As the icy winds of winter swept down from the north, the

weary voyagers discovered that the two-month voyage of rough seas and bitter

winds had taken them far north of their expected destination in the Virginia

colonies. They were far from home, with no one to greet them, no friendly house

to enter. As Nathaniel Morton's chronicle describes the scene:

Being now passed the vast ocean, and a sea of troubles

before them in expectations, they had now no friends to welcome them, no inns

to entertain or refresh them, no houses, or much less towns, to repair unto to

seek for succour; and for the season it was winter, and they that know the

winters of the country know them to be sharp and violent, subject to cruel and

fierce storms, dangerous to travel to known places, much more to search unknown

coasts.

Besides, what could they see but a hideous and desolate

wilderness, full of wilde beasts and wilde men? and what multitudes of them

there were they knew not: for which way soever they turned their eyes (save

upward to Heaven) they could have but little solace or content in respect of

any outward object; for summer being ended, all things stand in appearance with

a weatherbeaten face, and the whole country, full of woods and thickets,

represented a wild and savage hew.

If they looked behind them, there was a mighty ocean

which they had passed, and was now as a main bar or gulch to separate them from

all civil parts of the world.

Some of the party wanted to continue south but they were

overruled; these visionary pioneers had an appointment with destiny and they

stood fast.

The Mayflower Compact

The 102 settlers aboard the Mayflower hold a rightly revered

place in the history of America. Before disembarking, before even setting foot

on the new land, these settlers blazed a new trail in participatory government,

a trail that would guide a new nation toward democracy.

On November 21, 1620, the Pilgrims and other colonists met

in the cabin of the ship and forty-one men signed an agreement that became

known as the Mayflower Compact. This was the earliest attempt at

self-government in the New World. (Because women had few legal rights in those

days, only men signed the Compact.) The forty-one signers, in eight

sentences, brought to flower the religious and political thinking of

generations when they agreed to elect men to rule over them whom they would, by

consent, obey. This was the first little step toward the Constitution of the

United States of America.

The Vision of the Pilgrims

Question: What vision guided the Pilgrims aboard the

Mayflower when 379 years ago they landed in America? What was it that

brought them to the shores of the New World?

Answer: Divine Love was preparing a place for the

second coming of the Christ.

The Pilgrims had a vision of hope, a vision of freedom. They

hoped to form a nation where the government would be established according to

the Scriptures.

They had endured much and had a fair understanding of how

they wished to apply their understanding of Scripture to many situations,

including civil government.

William Bradford, second governor of the Plymouth Colony,

wrote in his diary:

A great hope and inward zeal they had of laying some

good foundation for the propagating and advancing the gospel of the Kingdom of

Christ in those remote parts of the world; yea, though they should be but even

as steppingstones unto others for the performing of so great a work.

(William Bradford, History of Plymouth Plantation: 16061646 ed.

William T. Davis, p. 46)

Verily, they were a "stepping stone" to

the eventual founding in human consciousness of the second coming of the

Christ, when they drew up and signed the document today called the Mayflower

Compact.

Signing of the Mayflower Compact,

1620

Artist: Percy Moran

Courtesy of

the Pilgrim Hall Museum, Plymouth, Mass.

Their Mayflower Compact, signed Nov. 21, 1620, before

the settlers even stepped ashore at Plymouth Rock, reads:

"In the name of God, Amen. We whose names are

underwritten....having undertaken for THE GLORY OF GOD AND ADVANCEMENT OF THE

CHRISTIAN FAITH...a Voyage to plant the first Colony....Do by these

Presents, solemnly and mutually, in the presence of God and of one another,

covenant and combine ourselves into a civil body Politick....In Witness whereof

we have hereunto subscribed our names at Cape Cod, the eleventh of

November...Anno Domini 1620."

The Mayflower Compact constituted the signers and

their families as a body politic. In eight short sentences it made a covenant

with God and each other to found a colony for His glory. The eventual outgrowth

of this little seed of Christian faith, called the Mayflower Compact,

would be the United States Constitution with laws that would

ensure liberty and freedom of religion for all.

These freedoms could only come about because God's

Constitution is always unfolding. The Mayflower Compact was one

step. Another would occur in 1787 when a good example of God's

Constitution would be given word--words which like the Bible's can do

no more for mortals "than can moonbeams to melt a river of ice" without the

spiritual background and spiritual trust in good.

Guided by the hand of infinite good, the Pilgrims were

helping prepare the needed spiritual background for the second coming of the

Christ. Even their seeming misfortunes were part of the plan of divine Mind.

The Pilgrims came to the new colonies to spread the gospel; by divine

intervention they were blown off course. Had they reached the destination

man willed for them they would never have enjoyed the

religious or civic liberty God had planned for them, since the Virginia colony

had its roots deep in the hierarchical, monarch-led Church of England. Had they

not been forced to face the wilderness relying only on each other they might

never have written the Mayflower Compact. An "indispensable step" would

have been lost.

The Pilgrims Land

Following the signing of the Mayflower Compact, the

weary voyagers sent out scouting parties along the coast, looking for a good

place to settle. On December 21, 1620, the Pilgrims reached Plymouth and on

December 30 a boatload of Pilgrims climbed off the ship and stepped onto

Plymouth soil. Only curious Indians lurked in the woods. Snow swirled at the

Pilgrims' feet, and the land looked hostile and desolate as icy winds howled in

the bare trees.

The Pilgrims' first act in the New World was to give thanks.

William Bradford, describing the first landing of the Mayflower at Plymouth

that December, writes:

Being thus arrived in a good harbor, and brought safe

to land, they fell upon their knees and blessed the God of Heaven who had

brought them over the vast and furious ocean, and delivered them from the

perils and miseries thereof, again to set their feet on the firm and stable

earth.... What could they see but a hideous and desolate wilderness, full of

wild beasts and wild men--and what multitudes there might be of them they knew

not. The season it was winter, sharp and violent, subject to cruel and fierce

storms. What could now sustain them but the Spirit of God and His

grace?

Of the Pilgrims' landing Mary Baker Eddy writes:

On shores of solitude, at Plymouth Rock, they planted a

nation's heart,the rights of conscience, imperishable glory. No dream of

avarice or ambition broke their exalted purpose, theirs was the wish to reign

in hope's reality--the realm of Love. (Pul. 10:10)

When first the Pilgrims planted their feet on Plymouth

Rock, frozen ritual and creed should forever have melted away in the fire of

love which came down from heaven.

The Pilgrims came to establish a nation in true

freedom, in the rights of conscience. (Mis. 176:20)

Perhaps some readers of this book will remember memorizing

(in grade school) Felicia Heman's poem, regarding the Pilgrims' landing:

And the heavy night hung dark

The hills and waters o'er,

When a band of exiles

moored their bark

On the wild New England shore

Aye, call it holy

ground,

The soil where first they trod!

They have left unstained what

there they found

Freedom to worship God!

The Bitter First Winter

The settler's first winter in the New World was a saga of

terrible suffering. When the Pilgrims arrived at Plymouth in December, many

were sick. The few able bodied among them had to build huts. Rowing from the

Mayflower to shore they had to wade the last few yards through frigid

waters. In wet wool and canvas clothing they labored on the frozen, snow

covered ground from dawn till dark, cutting trees for log huts. Gradually the

Pilgrims moved from the cold Mayflower into these even colder log

huts.

Food was scarce. Nearly half of the Pilgrims, including

their first governor, John Carver, died of cold, disease or malnutrition. The

other half were so weakened by hunger they scarcely had the strength to bury

the dead. This must have stunned and demoralized at least some of these valiant

Pilgrims.

The Pilgrims also lived in terror of being attacked by the

Indians with whom they had not yet become friendly. They buried their dead at

night so the Indians wouldn't become aware of how few Pilgrims were left, as

they feared this might encourage the Indians to attack. (The Indians had ample

reason to hate Europeans, but that is another story.)

Samoset and Squanto

At last, in March of 1621, the Pilgrims' steadfast trust in

God was rewarded. An Indian named Samoset visited the

Pilgrims. He had learned a few words of English from English sea

captains with whom he had traded goods, and had even sailed with them on their

ships. Pilgrims. He had learned a few words of English from English sea

captains with whom he had traded goods, and had even sailed with them on their

ships.

Samoset brought the settlers an invaluable blessing; he

introduced them to Squanto, an Indian who had lived in England and understood

the newcomers' language and ways. Squanto took compassion on the settlers, even

though he himself once had been enslaved by their countrymen. He gave the

Pilgrims corn and helped them plant it. He taught the colonists how to grow

other crops, and how to hunt and fish.

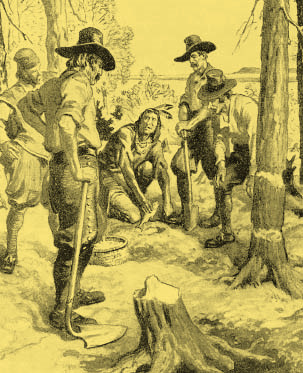

Samoset befriends the Puritans

Survival was the major issue of that first year, but with

Squanto's help the Pilgrims hung on until the fall crops brought in a good

harvest.

The First Thanksgiving

In autumn of 1621, with another winter approaching, instead

of begging God for more blessing, the Pilgrims'

profound

faith in God led Governor William Bradford to set aside a day for public

Thanksgiving in gratitude for the blessings already received. The Pilgrims were

heeding the many Bible references to the importance of "thanksgiving." profound

faith in God led Governor William Bradford to set aside a day for public

Thanksgiving in gratitude for the blessings already received. The Pilgrims were

heeding the many Bible references to the importance of "thanksgiving."

History tells us that Chief Massosoit was invited. He

brought 60 braves, 5 dressed deer and a dozen wild turkeys. Even popcorn helped

to celebrate this first great Thanksgiving Day, which lasted three whole days,

so deep felt and abounding was their gratitude to God.

Squanto helped the Pilgrims survive their first grim years

at Plymouth Colony. His wonderful work with the Pilgrims brought a relationship

of peace and helpfulness between the settlers and the Indians that would last

more than fifty years.

Squanto shows Puritans how to plant

crops.

Seeking freedom of the spirit, the Pilgrims courageously

carved a home out of what must have seemed a fierce, ruthless, ferocious,

unyielding, relentless and forbidding territory, that the Bible (Rev.

12:6) calls "the wilderness" that "the woman fled into," in fulfillment of

prophecy. (See S&H 565:29.)

The Mayflower brought a wonderful breed of human beings to

America. Longfellow in his poem about Miles Standish, writes, "God sifted out a

hundred and two seeds from the civilization of Europe to plant a new nation on

these shores."

What did they come for?

The Pilgrims came for one purpose--the propagation of the

gospel. The Mayflower's passengers were just middle-class people--unpretentious

tradesmen, farmers and laborers--but they were strong, rugged, and determined.

Far from home, put out in icy November with no houses, no food, and with the

specter of fearsome Indians and wild animals hiding in the woods, they

made it. No one should sneer at the rugged individualism that built

this country and the rugged way this country was founded.

The Pilgrims created a path for all to follow. Many years

later William Bradford said, "As one small candle may light a thousand, so the

life here kindled (in Plymouth) hath shown unto many, yea, in some sort, to our

whole nation." Thus did this sturdy remnant "on shores of solitude...plant a

nation's heart--the rights of conscience, imperishable glory...their's was the

wish to reign in hope's reality--the realm of Love."

The New England Federation

America is unique. It was divinely founded to make mankind

ready for the second coming of the Christ.

The Pilgrims were just one small settlement of many that

would spring up in America, drawn by the desire to worship according to the

dictates of their own conscience. The details of their faith and their

understanding of God, infinite good, varied, but each colony had a desire for

"the furtherance of so noble a work, which may by the providence of Almighty

God hereafter tend to the glory of His divine Majesty" (Documents of

American History, p.8).

The documents establishing the governments of these early

settlements always began in a manner showing their distinctive Christian

character, such as: "Forasmuch as it has pleased the Almighty God by the wise

disposition of His divine providence...to maintain and preserve the liberty and

purity of the Gospel of our Lord Jesus [Christ]...which according to the truth

of the said Gospel is now practiced among us..." (Ibid. "Fundamental Orders of

Connecticut," Jan. 14, 1639).

On May 19, 1643, several of the colonies decided to get

together and draw up a document they called The New England

Federation.

What did these colonies all have in common? Most of the

published material coming out of early America spoke clearly of God, Christ

Jesus, and the Holy Spirit. Their basis was I Cor. 3:11:

"For other foundations can no man lay than that is laid,

which is Jesus Christ."

Whereas we all came into these parts of America with one

and the same end and aim, namely: to advance the Kingdom of our Lord Jesus

Christ, and to enjoy the liberties of the Gospel in purity, with

peace....

These liberties didn't come all at once. Much was learned

the hard way. An example was the Pilgrims' experiment with communal farming,

which caused them to almost starve during the first two years.

Facing their third year of starvation, the elders of

Plymouth demanded the institution of a biblically based free enterprise system

in order to prevent the total destruction of their colony.

Governor Bradford tells us in his Diary that "this

made all hands very industrious, and gave far better content...."

This solution to poverty was another beacon pointing the

way. In Bradford's words: "As one small candle may light a thousand so the

light kindled here has shown unto many, yea, in some sort, to our whole nation"

(History of Plymouth Plantation).

That light did keep on shining, and the nation kept growing

and prospering. As Saint Francis of Assisi advised: "Start by doing what's

necessary, then what's possible, and suddenly you are doing the

impossible."

By 1732 America was made up of thirteen colonies. During

this first century God had blessed the colonies beyond measure. Then like a

slowly dying fire the spiritual light and faith began to dim. By the mid 1700's

what had been a blazing light had become only a faint glow. Had prosperity made

them forget God? It took the breath of God's spirit to revive our national

faith--to cause an awakening.

AMERICA book sections

Foreword | I |

II | III |

IV | V |

VI | VII |

VIII | IX |

X | XI |

XII | XIII |

Conclusion | Bibliography |